Likewise, the increase in interest rates here is insufficient without a firm commitment from the government to fiscal responsibility (Image: REUTERS/Amanda Perobelli)

Last Wednesday, the Federal Reserve ended a long period of expectations by announcing a significant cut in interest ratesadjusting them to the range of 4.75% to 5.00%. This movement marks the beginning of a cycle of monetary easing in the USAinitially scheduled for 2023 but repeatedly postponed. During the press conference, the Fed chairman, Jerome Powellstruck a cautious tone, describing the decision as part of a recalibration of monetary policy, aimed at ensuring a “soft landing” for the American economy.

Powell highlighted the absence of clear signs of recession in the near term, but avoided providing precise guidance on the central bank's next steps. He did, however, mention the updated dot-plot, which suggests two more cuts of 25 basis points by the end of this year and four additional reductions in 2025. Economic projections have also been revised, with the forecast growth of the GDP to 2.0% in 2024 and an adjusted unemployment rate to 4.4%, signaling a weaker job market.

If upcoming labor market data indicates a greater deterioration than anticipated, the Fed could consider an additional 75 basis point cut in 2024, which would strengthen risk assets globally. With the PCE index (personal inflation) coming in below expectations, the expectation of a cut of 50 basis points in November is reinforced, with the possibility of an additional reduction of 25 points in December.

This “soft landing” scenario suggests that falling interest rates could stimulate risky assets, especially in emerging economies like the Brazilwhich has faced the effects of high rates in developed economies. The metaphor of a “plane ready to take off” applies well to the situation: the assets benefiting from the fall in American interest rates are ready to move forward. What still stops us from getting on board?

Let's go in parts. In Brazil, the monetary policy response was opposite. The Monetary Policy Committee (Copom) decided to raise the Selic by 25 basis points, with the possibility of further increases until the end of the year. However, the country's biggest challenge goes beyond monetary policy: fiscal fragility is the main obstacle to economic stability. The most aggressive stance of Banco Centralaimed at containing inflationary pressures and re-anchoring expectations of inflationit will not be enough without an adjustment fiscal significant.

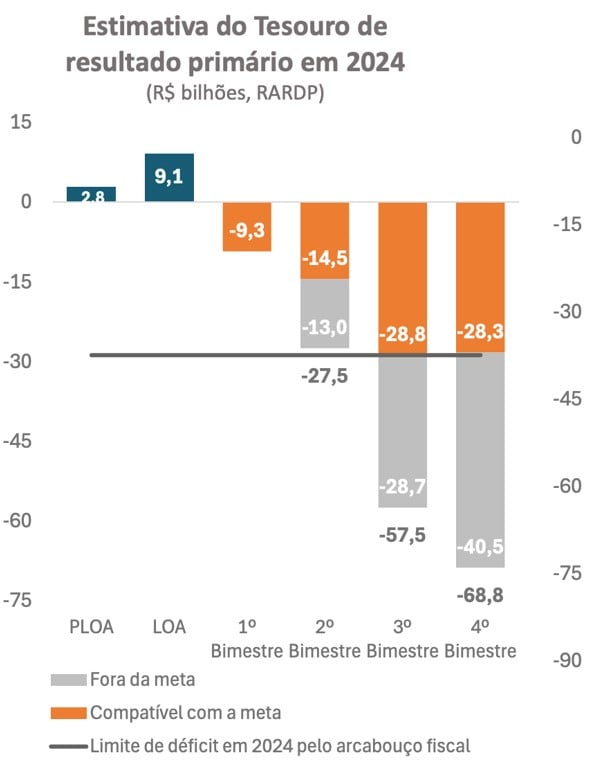

The fiscal situation worsened with the release of the government's bimonthly revenue and expenditure report, which frustrated expectations by not presenting the expected deep cuts. Instead, the government increased the budget blockade by just R$2.1 billion and reversed a previous contingency of R$3.8 billion, resulting in fiscal flexibility of R$1.7 billion. With expenses outside the framework estimated at R$40.5 billion, the projected deficit for 2024 reaches a worrying R$69 billion.

In this scenario, the minister's expectations Fernando Haddad to raise Brazil's credit rating, after meetings with the rating agencies Fitch, S&P Global and Moody's, seem excessively optimistic and far from reality. The idea that Brazil can recover investment grade by the end of next year sounds almost utopian, considering the current fiscal panorama.

Although the minister's statements brought brief relief to investors, worried after the release of the latest income and expenditure report, they do not address the deep structural challenges facing the country. To regain investment grade status, Brazil would need to climb two steps in the classifications of the main risk agencies, which have been reiterating the need for more consistent and lasting fiscal reforms.

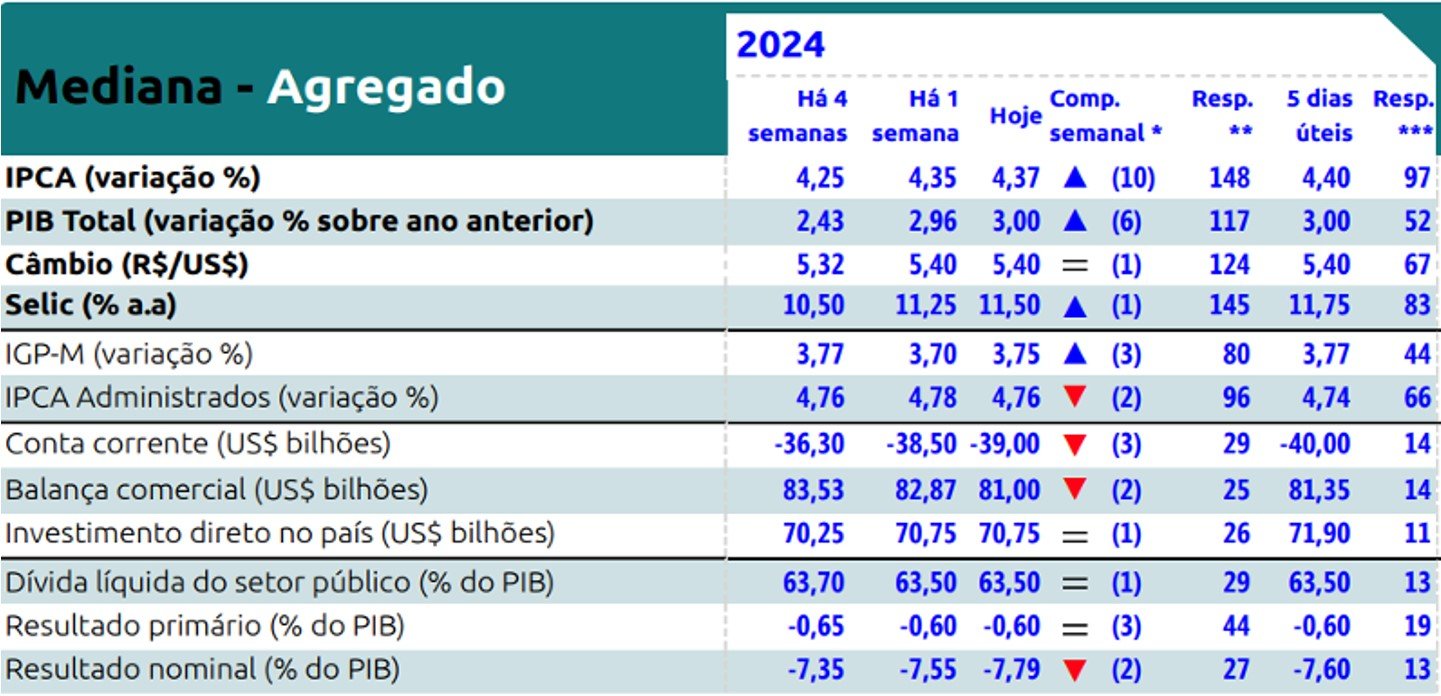

The market's response was immediate and mostly negative, reflecting frustration with the lack of concrete measures. This discontent, already present since the release of the report on Friday, gained even more strength on Monday, as highlighted by the Focus Bulletin. Growing distrust regarding the government's ability to meet its fiscal targets and, more importantly, to maintain its credibility with investors and rating agencies, has become even more evident.

The most recent bulletin brought an update to expectations for the Selic rate in 2024, with the consensus rising from 11.25% to 11.50%. This adjustment reflects Copom's stricter stance, motivated by higher-than-expected economic growth and increased fiscal risks. For 2025, the Selic projection remained at 10.50%, while inflation estimates for 2024 and 2025 were revised upwards.

The government's hesitation in implementing concrete and effective measures has negatively impacted market confidence. More flexible fiscal policy requires a more severe monetary response, which implies higher interest rates, harming assets such as actions. The latest Copom minutes emphasized the possibility of intensification in the monetary tightening cycle, in addition to recognizing that the Brazilian economy is operating above its capacity, which generates inflationary pressures due to the mismatch between supply and demand.

Although I believe that the Central Bank will continue to increase interest rates, I am skeptical about the intensity of this tightening. The projections that point to the Selic at 13% at the beginning of 2024 as the end point of the upward cycle seem questionable to me. Let's take it easy. Until then, we will have several variables at play, such as the continued fall in interest rates in developed economies, such as the USA, the adoption of new spending containment measures by the government — with the next primary revenue and expenditure assessment report scheduled for 22 November — and the upward trend in the real.

Regarding the exchangein addition to the interest rate differential that favors the real (cuts in interest rates in the USA and the increase in the Selic), economic stimuli from China have boosted the market for commodities and attracted foreign capital to the Brazilian stock market. As a result, bets against the real by foreign investors fell to US$65.7 billion, the lowest level since May. Despite signs of strengthening of the real, a more significant advance in the Brazilian currency, with the potential to approach R$5 per dollar, will depend on the government's firmer commitment to fiscal responsibility.

Contrary to this, the Ministry of Finance projects a worsening in the government's gross debt trajectory, despite new GDP growth projections. The fiscal situation is worrying, and there are doubts about whether the government fully understands the gravity of the scenario. To illustrate the challenge, the Independent Fiscal Institution (IFI), linked to the Federal Senate, revised its estimate for the government's gross debt, which is expected to reach 80.01% of GDP in 2024, an increase from the previous forecast of 78% .

By 2026, a more flexible monetary policy in the US could stimulate greater optimism in the Brazilian market. However, without a definitive solution to persistent fiscal problems, there is unlikely to be an easy “final solution.” As already highlighted, increasing interest rates alone will not be enough without a firm commitment from the government to fiscal balance.